Dignified, calm, introverted, soft-spoken (to the point of being inaudible), Jehan Daruwalla peered at you through thick glasses, his bushy eyebrows slightly raised. A lifelong insurance person, he was suddenly thrust, at age 65, into the editorship of the then leading Gujarati daily, the Mumbai Samachar. Most believed that Daruwalla would turn out to be a damp squib. When the octogenarian retired from editorship after 25 years, Daruwalla had galvanized the Parsi Press to an unimaginable extent.

Daruwalla had experienced poverty firsthand. And he hated those who exploited others or were corrupt. With equal passion, he detested the orthodox and lost not a single opportunity to lampoon the fundamentalists. Between this columnist (who was his assistant for around three years) and him, the "Parsi Tari Aarsi” Sunday column (PTA) invented some memorable terms — fruitcakes, lunatic fringe, heretic scum, cremate-ni-bungli, obscurantist humbug. Politeness flew out of the window, as the delighted Camas felt vindicated that PTA in English was making a much more meaningful impact.

Daruwalla had a clear-cut socioreligious reform agenda. He had faced personal humiliation in the offices of the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) as a beneficiary. He was like Caesar’s wife: above suspicion. After serving the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) honestly for decades, he enjoyed a sabbatical in Iran for more than a year, as a Persian scholar. This was cut short due to his beloved wife Hilla’s ill health. Even after his elevation as the editor, he lived a spartan life in a tiny charity flat of 400 sq ft (he never possessed a car and often did the cooking himself). His accumulated anger was unleashed against the corrupt, the pompous and fundamentalists. There was a bomb within him waiting to explode (this columnist was perhaps instrumental in happily igniting that bomb).

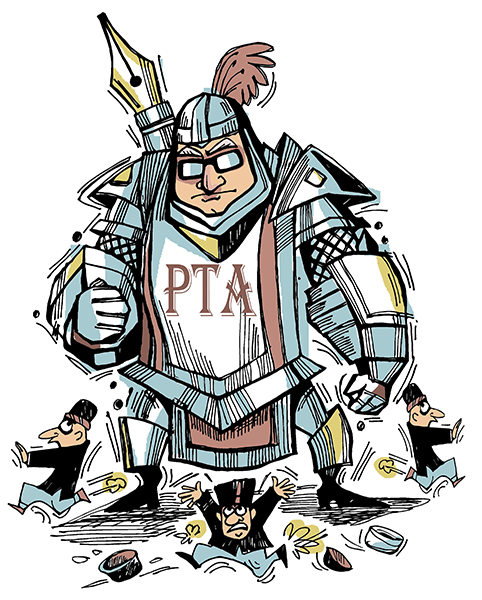

Illustration by Farzana Cooper

His relentless campaign against nepotism and possible illegal gratification in housing allotment by the BPP was brutal and effective. There was not much hesitation in naming persons, as he followed this columnist’s advice not to be too bothered about the niceties of hard evidence. This campaign resulted in the formation of the Committee for Electoral Rights (CER) and the introduction of the merit rating system in housing allotment. Daruwalla’s bête noires, BPP chairman B. K. Boman-Behram and BPP trustee Dr Nelie Noble (for being ultraorthodox), made inglorious exits.

PTA was candidly reformist. When the interfaith married Roxan Shah’s body was denied consignment at the Towers of Silence after her tragic death in an automobile accident, Daruwalla was furious. Tempers rose worldwide when a scholar high priest equated interfaith marriages with adultery. Daruwalla dubbed him an obscurantist humbug. PTA went at the issue hammer and tongs, week after week, until it was resolved in favor of the interfaith married ladies who had to submit an affidavit stating they had married under the Special Marriage Act and continued to follow the Zoroastrian faith. The women formed an association called the Association of Interfaith Married Zoroastrians (AIMZ), now moribund.

The next in the line of attack was the Athravan Education Trust or AET, a trust to train young practicing mobeds. Even admirers of Daruwalla thought that there was nothing wrong with the proposal and his ire was more on account of the people behind it [Dastur (Dr) Firoze Kotwal and Khojeste Mistree, founder of Zoroastrian Studies]. With the nitpicking skills of an insurance man, he made AET appear an unfavorable concept until it was finally dropped. The mainstream orthodox squarely blame him even today for obstructing the welfare of the mobeds. Mistree’s wife Firoza, as co-editor of The Collected Scholarly Writings of Dastur (Dr) Firoze M. Kotwal, observed: "All attempts at neutrality were discarded, and a unidimensional view of the issue was projected. There was little doubt that the attitude of the Parsi Press during the AET controversy reflected the growing interference of their owners, and from then onwards would reflect the opinions of their financiers and those with political clout; editorial independence would soon be a thing of the past.”

Insistence on disposal of the dead at the dakhmas despite the absence of vultures, gender equality for the children of interfaith married women, the right of Parsis to adopt, treating non-Parsi Zoroastrians on par with Parsis, open door policy for admission to places of worship, were Daruwalla’s pet issues. It was Daruwalla who made Joseph Peterson, a North American convert to Zoroastrianism, renowned. Daruwalla also full-throatedly supported Ali Jafarey, the so-called Islamic intervener in Zoroastrianism, much to the chagrin of the orthodox.

While Daruwalla had impeccable personal integrity, he was certainly not dispassionate in his analysis. His biases bristled all over his columns. He was delighted when those he thought undesirable were thrown off their pedestal. While history will proudly record his stellar contribution to reform, he was prejudiced all right. He had a mental blacklist of bad Parsis which would make interesting reading but for the fact that some of them are still alive.

In his mid-90s Daruwalla mellowed as age and health took their toll. From 2002 to 2012, after his retirement, the PTA, under a new columnist (Berjis Desai — editors), continued to broadly toe Daruwalla’s socioreligious thinking. It rooted for adult franchise to elect BPP trustees; gave considerable space to Dhun Baria and her crusade against the state of affairs in the dakhmas; turned distinctly hostile to the Dinshaw Mehta-WAPIZ (The World Alliance of Parsi Irani Zarthoshtis) alliance; and it empathized with the so-called "renegade” priests. The new columnist had his own share of biases and predilections galore. This writer ought to know!

Parsiana, undoubtedly the most professional of all Parsi publications, albeit with a liberal bias like The Guardian of London, set exacting standards for itself in reporting accuracy and admission of errors. Its columns were open for those criticized who cared to respond, so long as such response was rational and temperately worded. It held up a mirror to the community by buttressing its arguments with statistics, such as to highlight the irreversible demographic decline (feebly dismissed by the mainstream orthodox as paranoia and twisting the inferences). The traditionalists largely chose to ignore, or pretended not to read, Parsiana, which made it appear as if their views were not being published. Of course this publication too clearly has its philosophical biases which however are not in the face, as was the case with the other newspapers.

From the red hot Parsi publications of the last many decades, today we have none left, with the singular exception of this publication. Mumbai Samachar no longer has a Parsi column. Jam-e-Jamshed and Parsi Times hardly express any views. Newsletters like Parsi Junction and Pol Khol Sacchu Bol merely incite or amuse. The occasional Parsee Voice does espouse the fundamentalist cause with some vigor but is read by few outside their core group. However, one thing has remained constant, namely, that there has never been a dispassionate chronicler of affairs Parsi. Perhaps that is an impossibility. Wish though that there were more chillies and less stale broccoli.

Berjis Desai, lawyer and author of Oh! Those Parsis, and recently Towers of Silence, is a chronicler of the community.